If you’ve followed my blog for any length of time you should be familiar with my view that the military justice system is broken.

There’s nothing to fix.

The military police are hopelessly compromised.

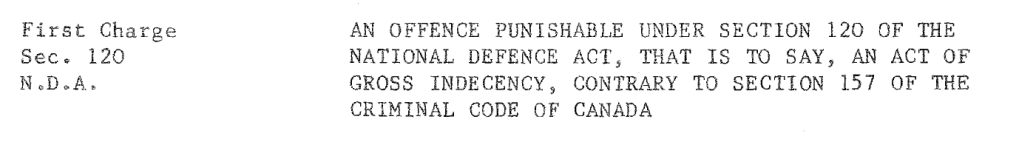

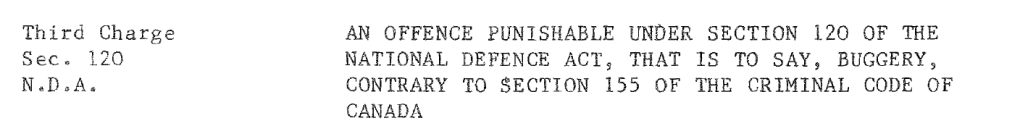

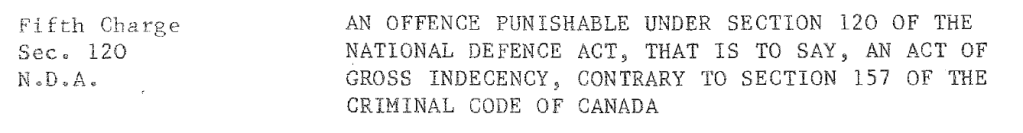

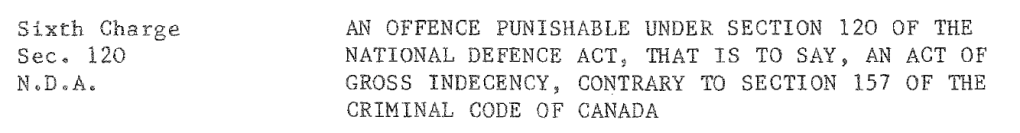

I am not going to speak to the innocence or guilt of the member that was subject to these charges. I am just questioning how the CFNIS thought that they were ever going to get a conviction in civilian courts.

It’s not the individual members. It’s a structural thing.

Because the military police are comprised of soldiers that are subject to the code of service discipline and that must obey the lawful commands of their superiors there is no reliable way to guarantee independence from the chain of command.

Because all members of the Canadian Armed Forces are required by law to obey the lawful commands of their superiors, how can they refuse a command to not follow a lead, or to not write specific information in a document, to not investigate certain leads, to not expand the scope of an investigation.

Are members of the Canadian Armed Forces permitted to or required to consult a legal officer in the Office of the Judge Advocate General to see if a command is lawful or unlawful?

What happens if the command comes from high up the chain of command? It’s not like a commanding officer has to explain to their subordinates where in the overall chain of command a command originated from.

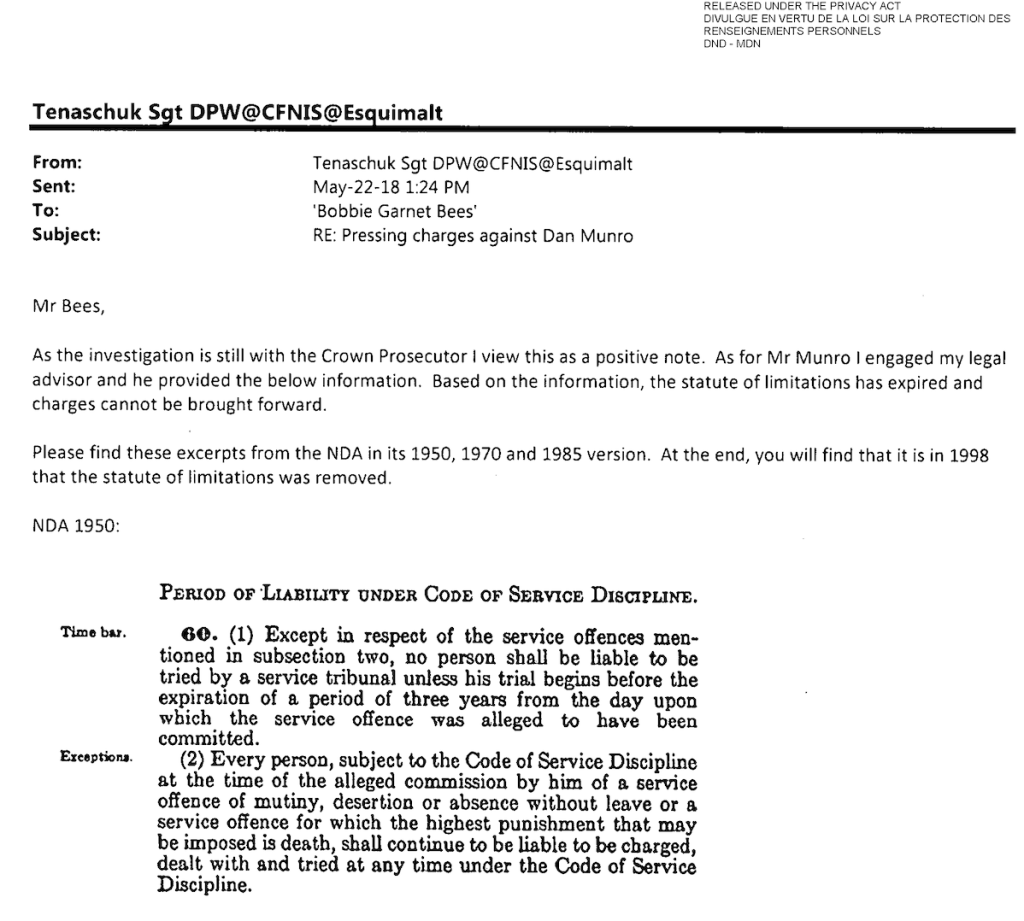

I am still trying to ascertain how the CFNIS ever thought that they would be able to successfully bring charges against a former member of the Canadian Armed Forces for a Code of Service Discipline offence that occurred in 1989.

As this alleged sexual assault involved two members of the Canadian Armed Forces on a defence establishment, this matter was automatically in the jurisdiction of the military justice system. That’s how the National Defence Act was written back in 1989 and that’s how the National Defence Act is still written to this day.

The problem for this matter, and how I can’t understand that it actually made it as far as court is the “summary investigation flaw” and the “3-year-time-bar”.

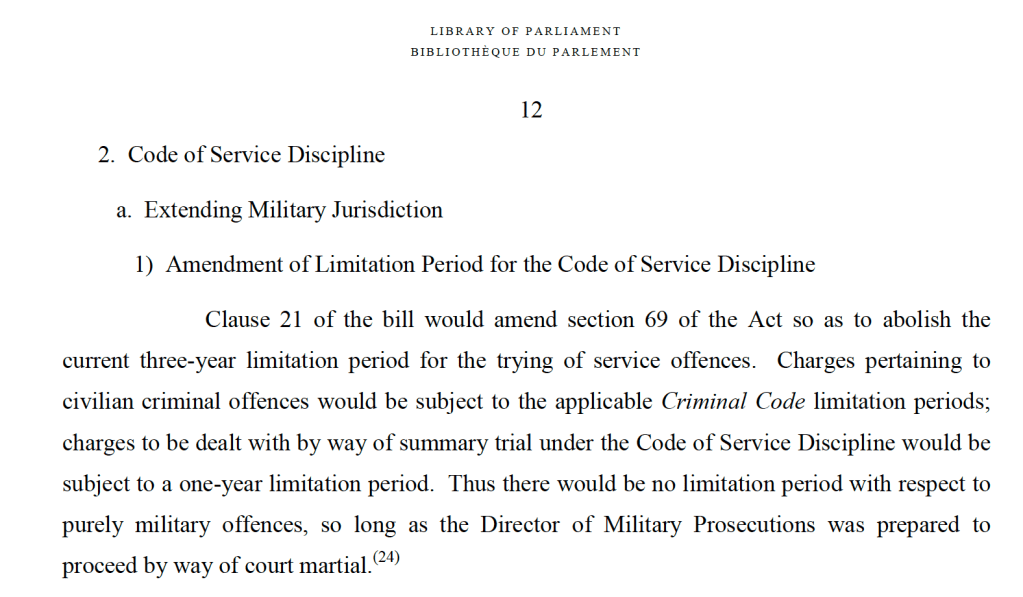

In December of 1998, with the passing of Bill C-25 “An Act to make Amendments to the National Defence Act” the 3-year time bar, and the requirement for a subsequent investigation by the commanding officer were removed from the National Defence Act.

When Bill C-25 was passed, there was no legislation passed to retroactively undo the effects of the 3-year time bar, and the requirement for a summary investigation after the laying of charges.

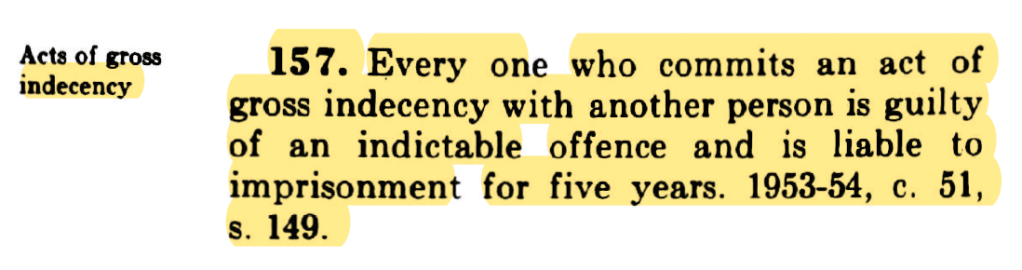

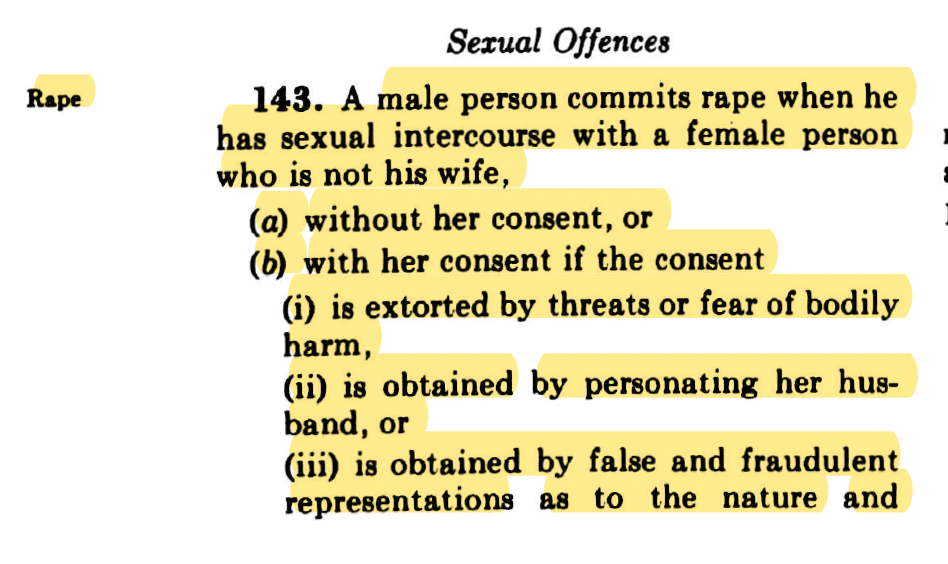

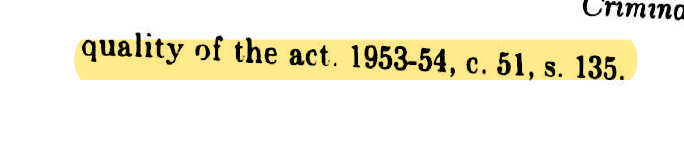

Yes, I fully understand that in 1989, sexual assault were not a service offence that the military could conduct a service tribunal for. Sexual assaults had to go to the civilian courts.

However, that’s not how it actually worked.

The commanding officer would have to APPROVE the charges before they could go anywhere.

Murder, Manslaughter, and Sexual Assault were not exempted from review by the commanding officer of the accused.

Let’s read the important section together. But before we do, remember that Bill C-25 removed this section from the National Defence Act, it did not remove this requirement retroactively from the National Defence Act.

d. Commencement of Proceedings (Clause 42: New Sections 160 to 162.2)

Sections 160 to 162 of the Act would be replaced by new sections 160 to 162.2. The key changes from the existing system in this area would be the proposed elimination of the requirement for an investigation after the laying of a charge (see section 161 of the Act) and the proposed elimination of the commanding officer’s power to summarily dismiss charges under the Code of Service Discipline (see section 162 of the Act).(35)

Currently, a commanding officer has the authority to dismiss, at the outset, any charge under the Code of Service Discipline. This includes not only all offences of a military nature, but also all civilian offences incorporated by reference into the Code of Service Discipline (see sections 130 and 70 of the Act), regardless of whether or not the commanding officer would have the authority to try the accused on the charge. (36) Pursuant to section 66(1) of the Act, the effect of a decision by a commanding officer to dismiss a charge is that no other authority –military or civil – can thereafter proceed against the accused on the charge or any substantially similar offence arising out of the same facts.(37)

This is a pretty damning statement “regardless of whether or not the commanding officer would have the authority to try the accused on the charge“. Do you know what charges commanding officers could not conduct a summary trial for?

Murder

Manslaughter

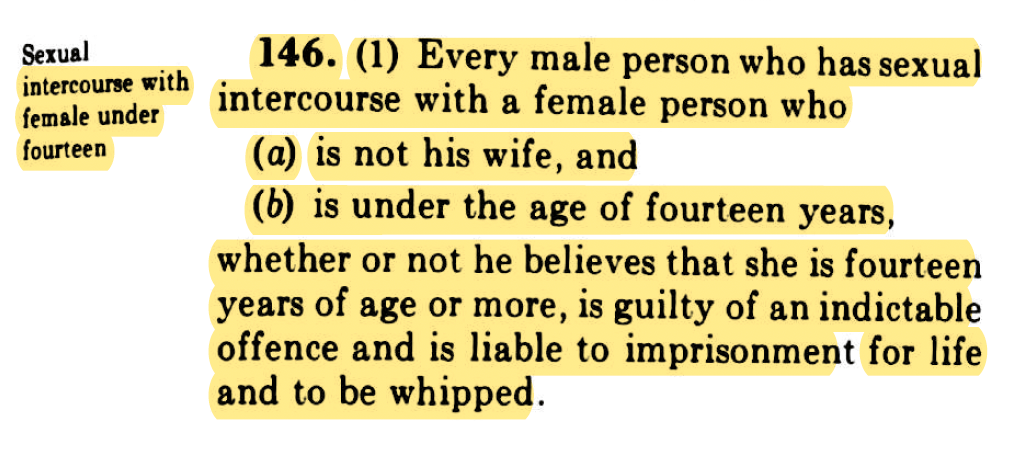

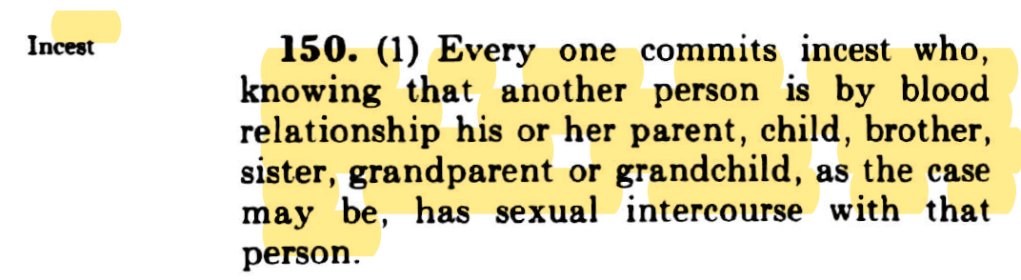

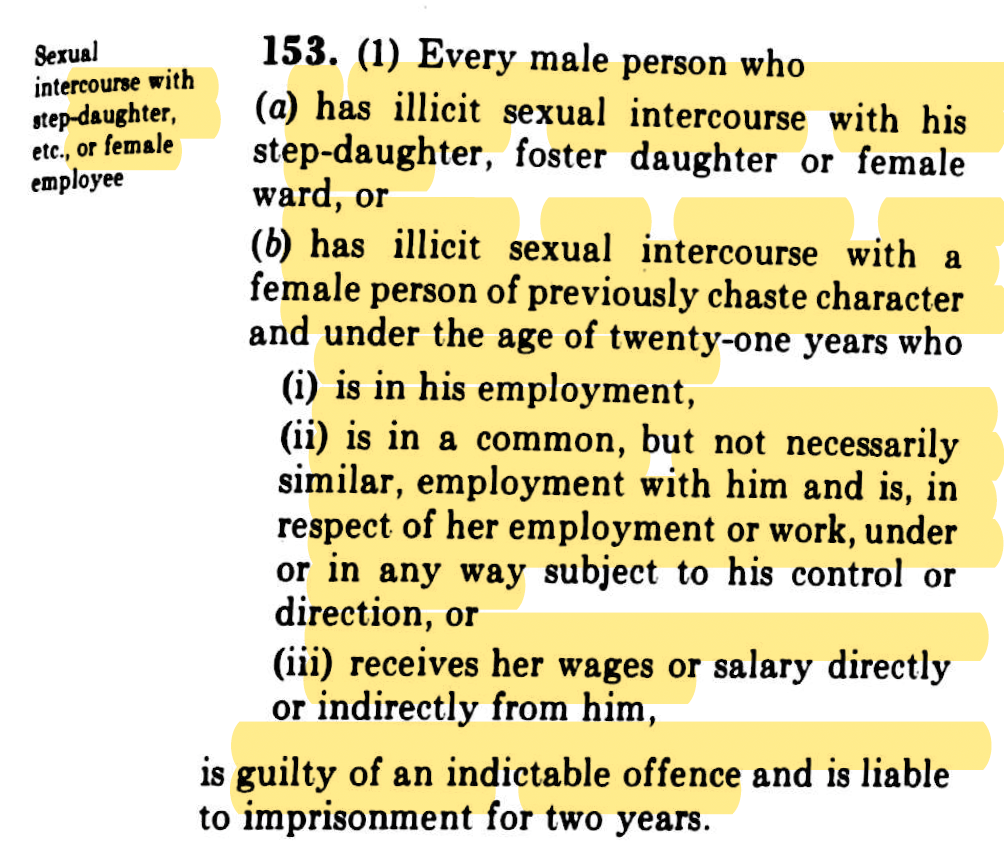

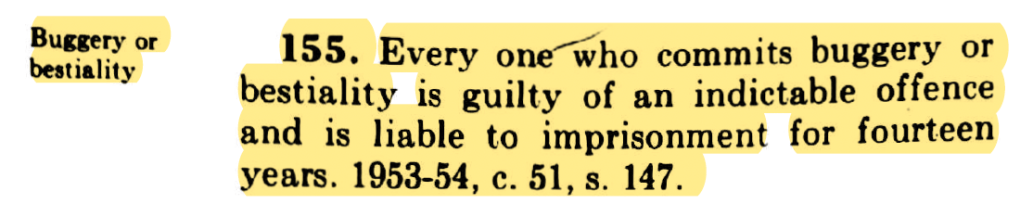

Rape( 1950 – 1985),

Sexual Assault (1985 – 1998)

If a member of the Canadian Armed Forces were arrested, investigated, and charged today for a historical offence that occurred in 1989, why would they give up the protections afforded to them by the National Defence Act in 1989?

What the above section states in plain English is that after a member of the Canadian Armed Forces is charged with a service offence, even a service offence comprised solely of criminal code offences, the commanding officer of the accused was required to conduct a summary investigation. The commanding officer could cause the charges to proceed to either a military tribunal or a civilian tribunal -or- the commanding officer could dismiss the charges. And once dismiss, that was it, those charges could never be brought again.

Commanding officers were not required to check with a legal officer (lawyer) until November of 1997 when commanding officers were required to get the okay from a legal officer prior to dismissing charges that had been brought against their subordinate.

Who in their right fucking mind would give up that protection?

The courts in Canada have been very clear that a person arrested for a historical crime has to be charged with offences that existed at the time the offence was alleged to have occurred. The person is also to be dealt with as the justice system existed at the time. The general exception to this is that corporal punishment and death are no longer allowed as punishments.

As I’ve said before, these commanding officers were not lawyers, they had no legal training, and no legal background. Yet they were acting as Crown Prosecutors.

Did these commanding officers ever act inappropriately?

You betcha.

The Somalia Inquiry was called because of the massive coverup in the death of Shidane Arone and the fact that it was only two junior members of the Canadian Forces that were ultimately held responsible for Arone’s death. The Somalia Inquiry found that chain of command interference made it impossible to ever discover the truth about who knew what and when they knew it.

The Canadian Armed Forces tried to paint this whole matter as being due to a lack of discipline within the Canadian Airborne Regiment, but the rot was baked into all aspects of the Canadian Armed Forces due to the power of the chain of command.

So, how does this affect modern day prosecutions?

I can’t see how these charges are making it to court.

What person would give up legal protections that they enjoyed at the time of the offence?

What person would give up the ability to plead their matter to a commanding officer and to enjoy that commanding officer’s discretion to dismiss the charges?

And quite frankly there is one other horrible aspect of this that I haven’t really focused on too much, but it’s Section 66(1) of the pre-1998 National Defence Act.

Prior to 1998 any charge for a service offence that had been dismissed against a member of the Canadian Armed Forces by the commanding officer of the accused could never be tried again by either a military or civilian tribunal. Tribunal in this sense means a military courts martial or a civilian criminal trial.

What this means, is if Captain McRae’s commanding officer, Base Commander Colonel Dan Munro, was presented with charges that indicated that Captain McRae had molested more than just my babysitter and Col Munro had dismissed all other charges for whatever reason, those charges that were dismissed could never be brought against Captain McRae at a later date.

Remember, it was the babysitter’s father himself that confirmed in 2015 that the military police informed him in 1980 that they had the names of 25 children that had been molested by Captain McRae.

And remember that it was none other than a retired military police officer with direct connections to the investigation in 1980 that told me in 2011 that the “brass” had dismissed numerous charges that had been brought against Captain McRae.

And also remember that Angus McRae was alive in March of 2011 when I made my complaint to the CFNIS. McRae didn’t die until May 20th, 2011, which was well after the 2011 investigation was underway.

Unbeknownst to me when I made my complaint, the CFNIS had in their possession the 1980 CFSIU investigation paperwork that would have explained to the CFNIS in 2011 just how horrible of a mess this entire matter was in 1980 and that it was my babysitter being investigated for molesting children that led to Captain McRae’s abuse of children being exposed.

However, no matter what the CFSIU investigation paperwork had to say, Section 66(1) of the pre-1998 National Defence Act presented one helluva dilemma to the CFNIS in 2011.

No matter how much evidence the CFNIS uncovered in 2011 which indicated that McRae was the ultimate “ring leader” and that the babysitter was his “agent”, the CFNIS would never be able to lay charges against Captain McRae while at the same time the CFNIS would have been able to charge the babysitter for everything he had done. The babysitter, being a military dependant, would never have enjoyed the same legal protections that Captain McRae enjoyed. Not because his actions were less serious, but because the law treated him differently

And that’s why I can’t see any member of the Canadian Armed Forces being willing to go to court to face service offence charges for acts that occurred prior to 1998.

I have tried numerous times over the years to have the Ombud for the Canadian Forces look into this matter. I have never received any interest.

I have even contacted the Military Police Complaints Commission and Ihave asked them to look into the matter. Not interested in the slightest.

And then of course there’s the DND, the CAF, and the MoD. They’ve been asked to look into this matter to see if it has any effect on the reporting of child sexual abuse that occurred on base prior to 1998. None of these agencies seem to have any interest in this. It’s almost as if they live by the principle that if they don’t open their eyes, they don’t have to acknowledge any historical crimes.