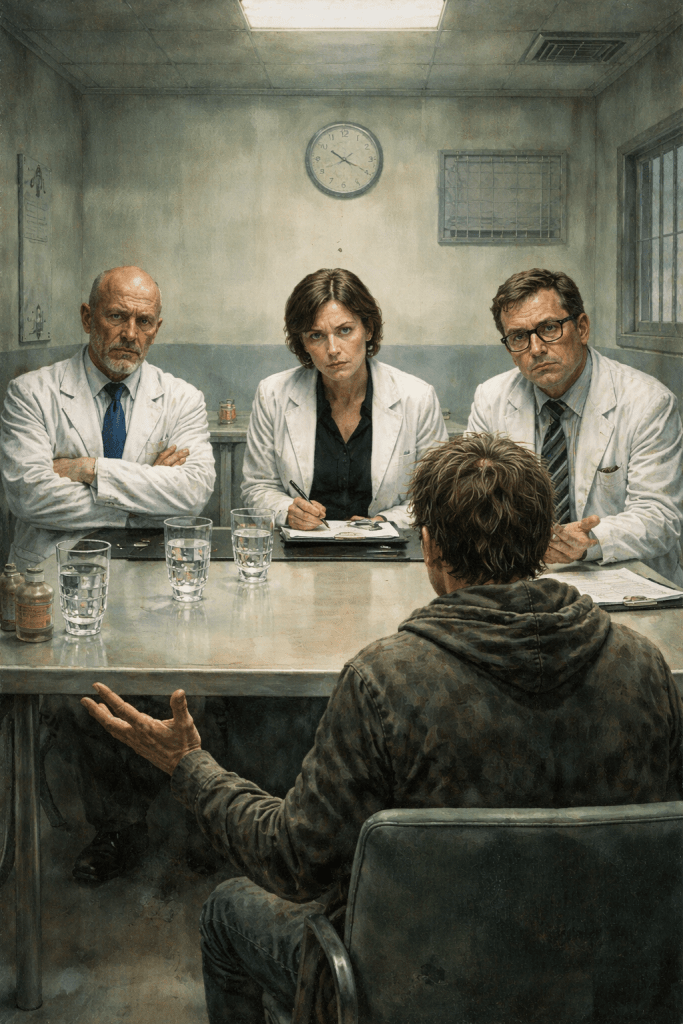

The worst offenders in the world for the “just smile and be happy” attitude are usually those that ought to know better such as psychiatrists and psychologists.

The problem that I have with psychiatrists and psychologists is that they occupy a position of authority that is rarely questioned and often poorly justified

In Most other fields of medicine, the cause of the problem can be easily determined, the matter can be dealt with, and the results of the treatment can be analyzed and quantified.

You feel depressed?

Have you tried not feeling depressed?

If you’re still feeling depressed then it’s your fault.

Here, have some meds.

How do they work?

We don’t know, but they seem to have something of a desirable effect, no?

What, you don’t like being numb or spaced out?

That’s okay, your depression isn’t bringing us down, so we feel better about ourselves.

We will tell you how to feel.

And that’s what psychiatric treatments are all about. How to make the patient behave in such a way as to mask their issues so as to make society feel comfortable around them.

And holy hell, if you don’t match their preconceived ideas of what someone suffering from major depression should be presenting as, you get laughed out.

I got laughed right out of the emergency mental health program at Vancouver General Hospital. I went in for an “emergency” consultation one day after my family doctor recommended that I go there as they might be able to help.

Got interviewed.

You could see that once I brought up the issues that I was having with depression, how long that I had the depression, and what triggered the depression the doc was already writing me off as some sort of nutcase that was wasting his time.

Head shrinkers work in a realm of medication that is analogous to priests and the soul. Head shrinkers can claim to cure patients of mental illness while at the same time not actually being able to cure patients.

People ask why depression isn’t taken as seriously as other mental illnesses.

And the honest answer is uncomfortable, because it has nothing to do with severity.

Depression is ignored because it’s common.

Because it’s mostly invisible.

Because it’s hard to prove.

Because it unfolds slowly instead of spectacularly.

And because it’s deeply inconvenient to the way psychiatry is structured.

Those traits make it administratively boring and professionally threatening at the same time — even while it destroys lives.

Psychiatry, like most institutions, responds best to disruption. If someone has schizophrenia or acute bipolar disorder, the room knows it. Conversations stop. Social rules break. Emergency systems kick in. There’s a clear before and after. Something undeniable has happened, and the system is built to respond to that.

Depression doesn’t do that.

Depression shows up as exhaustion. Flatness. Withdrawal. People still show up to work. They still answer questions. They still know exactly what’s happening — sometimes more clearly than the people treating them. They function just enough to be ignored.

Clinically, depression doesn’t demand the floor. And institutions respond to disruption far more reliably than they respond to erosion.

There’s also something psychiatry almost never says out loud:

Depression threatens professional authority.

A depressed person is often not delusional. They’re coherent. Consistent. Sometimes uncomfortably accurate. They can name power imbalances, injustice, loss, futility — and they don’t get better just because someone with a title tells them to.

With schizophrenia, a clinician can say, “Your perception is disordered.”

With depression, the question becomes, “What if their perception is accurate — and the system is the problem?”

That’s destabilizing for a profession built on expertise, correction, and the assumption that insight flows one way.

Then there’s the systems reality. Depression is cheap. Chronic depression is unprofitable. Treatment-resistant depression is a bureaucratic dead end. There’s no biomarker. No scan. No test result that ends the conversation.

So the system falls back on what it can process: short questionnaires, medication trials, surface-level therapy, maintenance instead of resolution. Depression gets reframed as background noise — something to manage, not something to confront.

Modern psychiatry is optimized for stabilization, risk management, symptom reduction, and throughput. Depression often asks for things that don’t fit that model at all: meaning. Reckoning. Grief without a deadline. Acknowledgment of irreversible loss.

That kind of suffering doesn’t scale. It doesn’t fit productivity metrics. So it gets softened, minimized, or relabeled as “mild,” “situational,” “manageable,” or “just part of life” — none of which reflect the lived reality of severe depression.

Cultural bias leaks in too. Depression overlaps with states society already moralizes: sadness, fatigue, withdrawal, hopelessness. Even in clinical spaces, those reflexes creep back in — try harder, be grateful, stay positive, others have it worse.

Psychiatry didn’t fully uproot those attitudes. It absorbed them.

So depression becomes this strange middle category: serious enough to medicate, but not serious enough to really face.

And then there’s the darkest reason — the one that actually matters.

Depression forces clinicians and systems to confront something they desperately avoid: some suffering isn’t fixable. Not every life can be restored. Not every wound closes. Not everyone gets their future back.

Taking that seriously would require humility. Limits. Grief on the clinician’s side of the table.

So instead, depression is managed. Normalized. Quietly deprioritized. Not because it’s small — but because fully acknowledging it would force the system to change how it understands itself.

That’s the truth.

Depression isn’t brushed off because it’s minor.

It’s brushed off because it doesn’t validate authority, doesn’t resolve cleanly, doesn’t perform illness dramatically, and often tells the truth too clearly.

Another issue with depression is people who live with depression while estranged from their families are fighting a different battle than those who come from supportive homes — and it’s one that often goes unseen.

When family is absent or unsafe, there’s no built-in safety net. No one to notice gradual decline. No one to step in during crises. No one to help navigate appointments, paperwork, finances, or recovery itself. What others experience as “support” — a couch to sleep on, a ride, a meal, someone to advocate for them — simply doesn’t exist.

Depression in isolation also removes emotional legitimacy. People from functional families are often believed sooner, taken more seriously, and given more patience. Those who are estranged are more likely to be questioned, minimized, or quietly blamed — as if the absence of family support says something about their character rather than their history.

There’s also the exhaustion of self-containment. When you’re alone, every setback has to be handled internally. There’s no place to fall apart safely. No shared memory of who you were before things went wrong. Healing becomes not just about managing symptoms, but about surviving without witnesses.

These aren’t minor disadvantages. They’re structural barriers. And pretending everyone starts from the same place only deepens the gap between those who suffer with backup — and those who have to carry everything themselves.

As I’ve said before, it wasn’t that nobody knew that I was struggling with depression in the aftermather of the Captain Father Angus McRae sex scandal on Canadian Forces Base Namao.

What follows is not speculation, but based on contemporaneous records and correspondence from that period.

My father knew, Captain Terry Totzke knew. Fuck, the entire chain of command right up to base commander Colonel Dan Munro knew.

And from the evidence presented in my paperwork from back then, the goal of the Canadian Armed Forces was to minimize the risk of exposing the scandal that occured on CFB Namao to the general public.

And I feel safe in implicating the Canadian Armed Forces as a whole as Captain Totzke wasn’t following the orders of my father Master Corporal Gill, it was the other way around. And Captain Totzke, being bound by the NDA to obey the lawful commands of his superiors would have been following commands from higher up.

So, sacrifices had to be made.

And my mental health was one of those sacrifices.