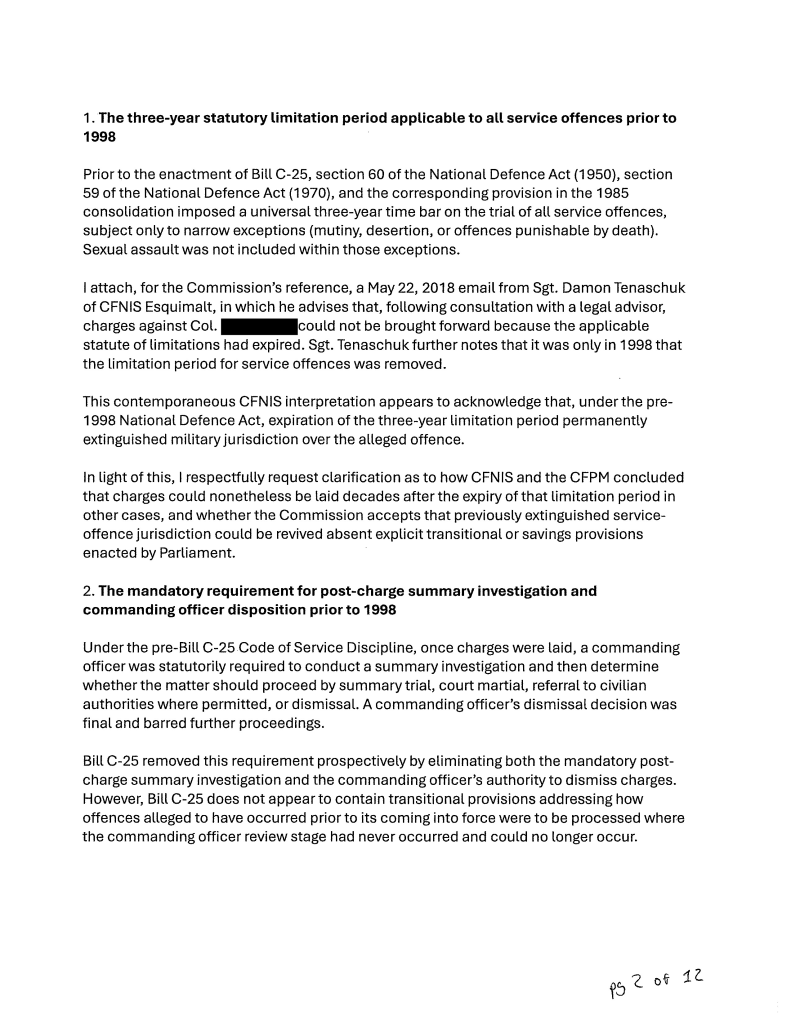

For all of the bitching and complaining that the Military Police Complaints Commission does about the Canadian Forces Provost Marshal and the Canadian Forces National Investigation Service, you’d think that the MPCC would show a little interest in talking to the CFPM and the CFNIS about just how exactly the Provost Marshal and the Military Police avoid the pitfalls presented by the pre-1998 summary investigation flaw and the 3-year-time-bar-flaw.

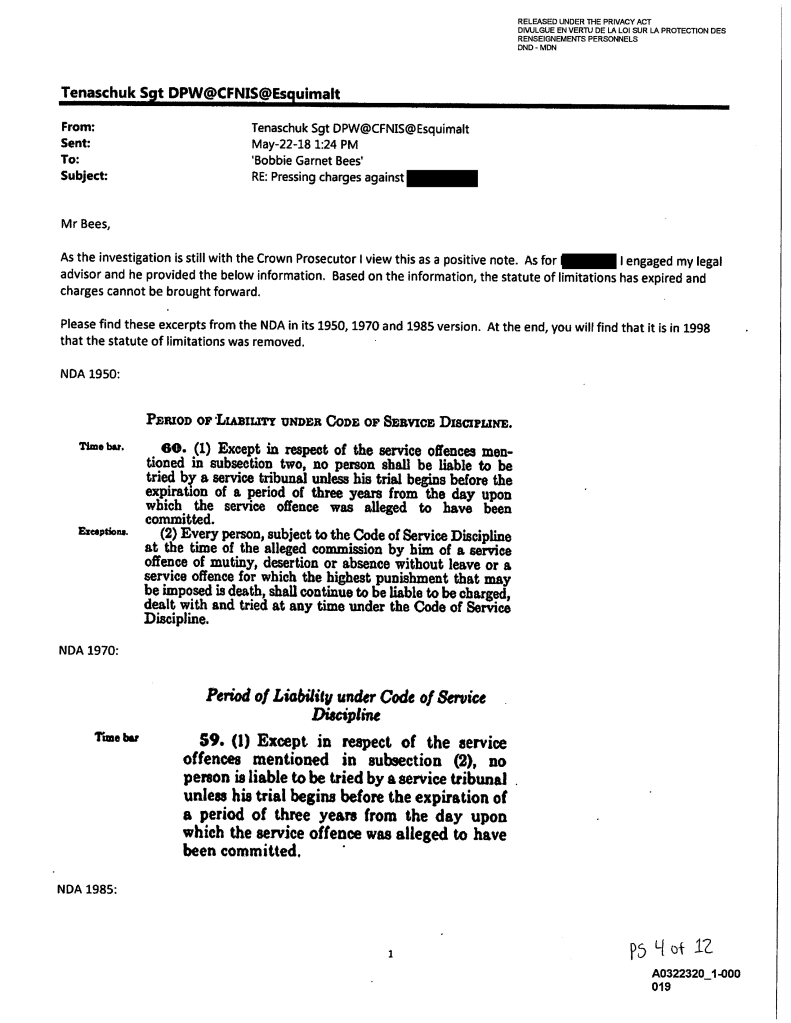

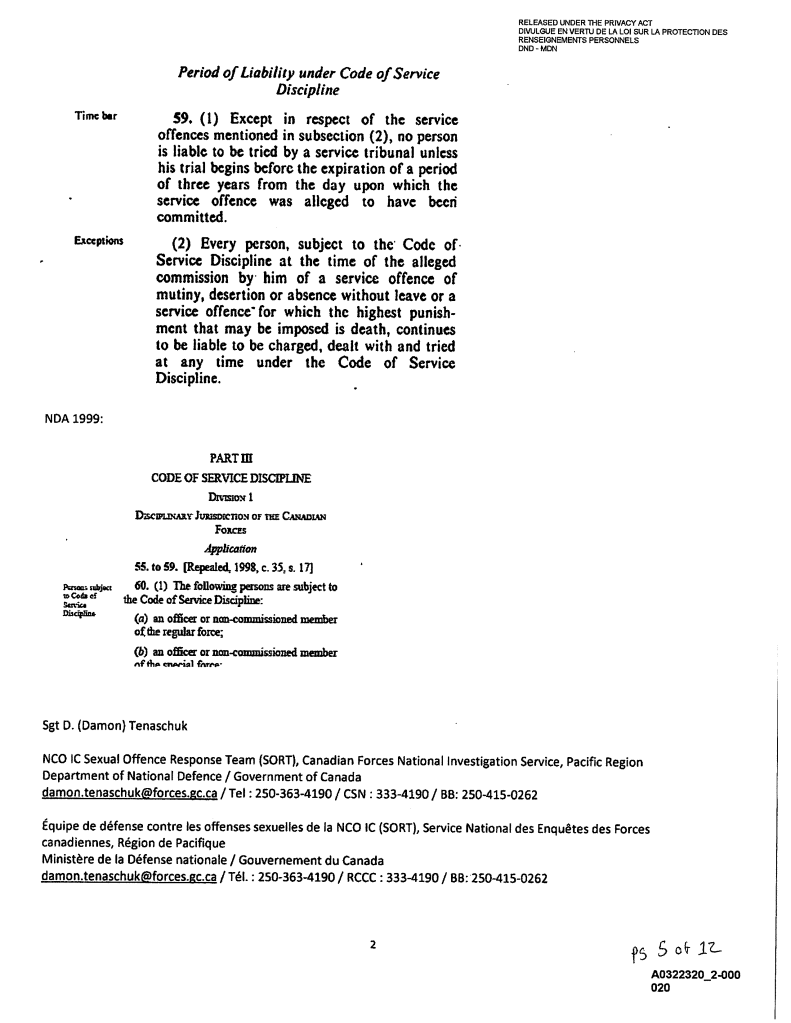

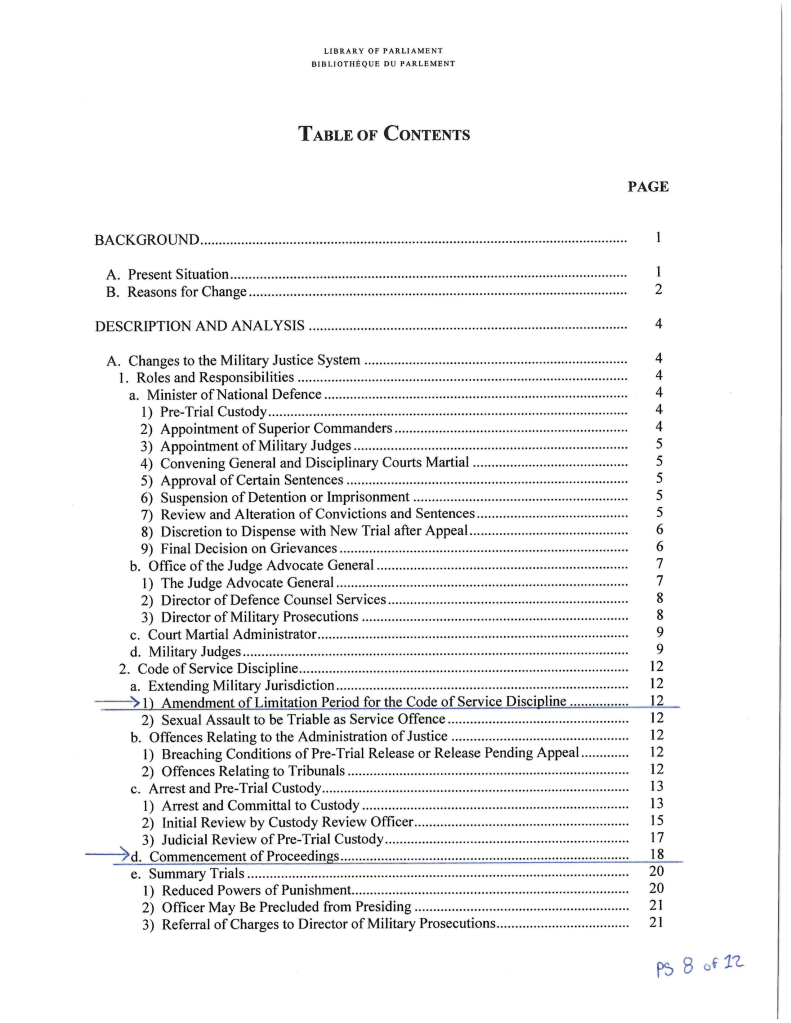

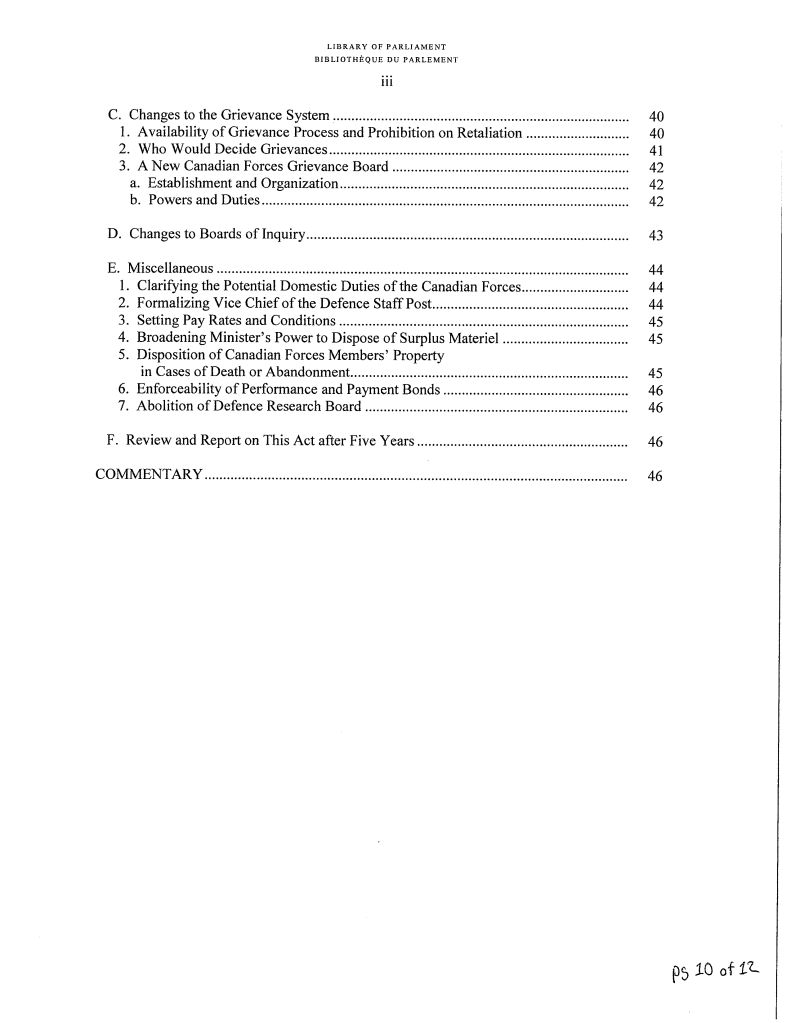

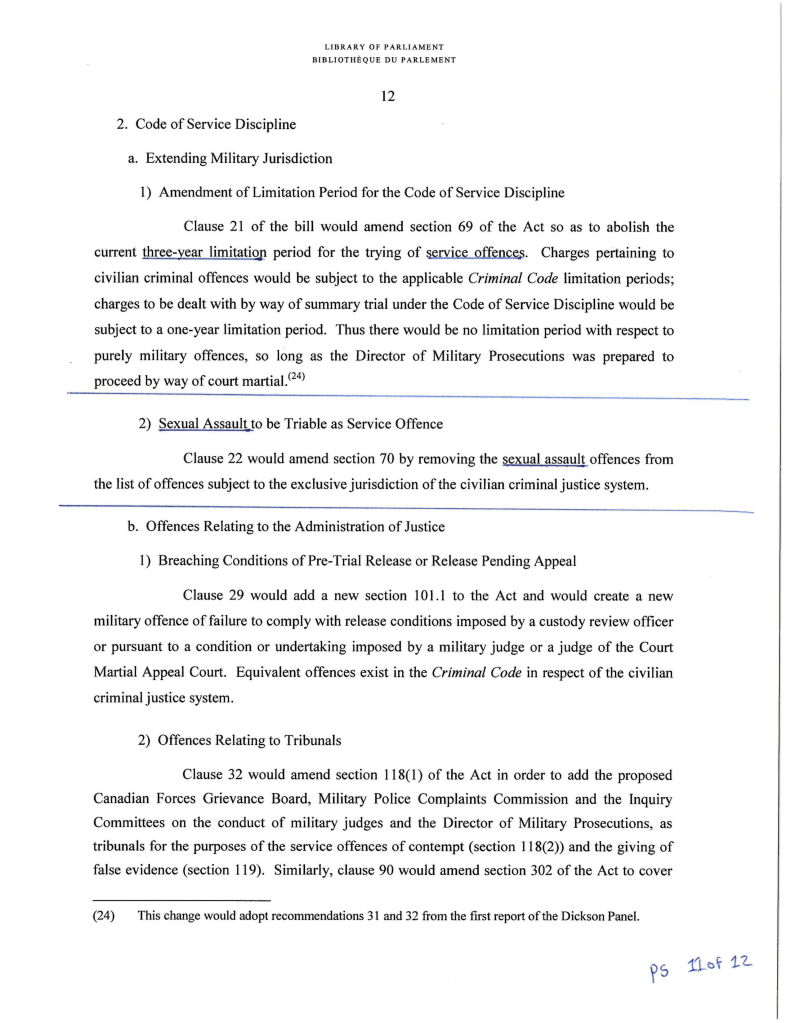

When Bill C-25 ” An Act to Make Amendments to the National Defence Act” was passed in 1998, it removed the 3-year-time-bar from the National Defence Act and it removed the requirement for Commanding Officers to conduct Summary Investigation of the charges brought against their subordinates.

When the 3-year-time-bar was removed from the NDA in 1998, Bill C-25 said that current Criminal Code limitations, if any, would apply to service offence charges comprised of Criminal Code offences.

Bill C-25 also said that there was no longer a need for the review of charges by the commanding officer of the accused via a Summary Investigation. Going forward all charges would be referred to a Military Director of Prosecutions.

But what Bill C-25 didn’t concern itself with is what happened to service offences that occurred prior to the bill coming into effect.

Bill C-25 only applied to Service Offences after the date the Bill became law. Bill C-25 did not apply retroactively to service offences committed prior to 1998.

In the past, when I’ve asked the CFNIS and the Provost Marshal how they can bring forth charges for service offences when the 3-year-time-bar has obviously expired, all I get is a “trust me” response. I’m never directed to any Act of Parliament that allows for the retroactive removal of the 3-year-time-bar prior to 1998.

I for one can’t understand how any suspect charged in the modern day for any service offence that occurred prior to 1998 would give up the protection of the 3-year-time-bar.

The 3-year-time-bar is the case killer for any service offence that occurred prior to 1998.

Now, I know that there will be those that say that “Service Offence” are only military related.

That’s not true.

A service offence is not only related to charges of a military nature, but to all criminal code offences that are committed in relation to a defence establishment or defence material by a person subject to the Code of Service Discipline at the time of the offence.

And if the 3-year-time-bar didn’t kill off the prospect of charges, the requirement for a summary investigation after the laying of charges would.

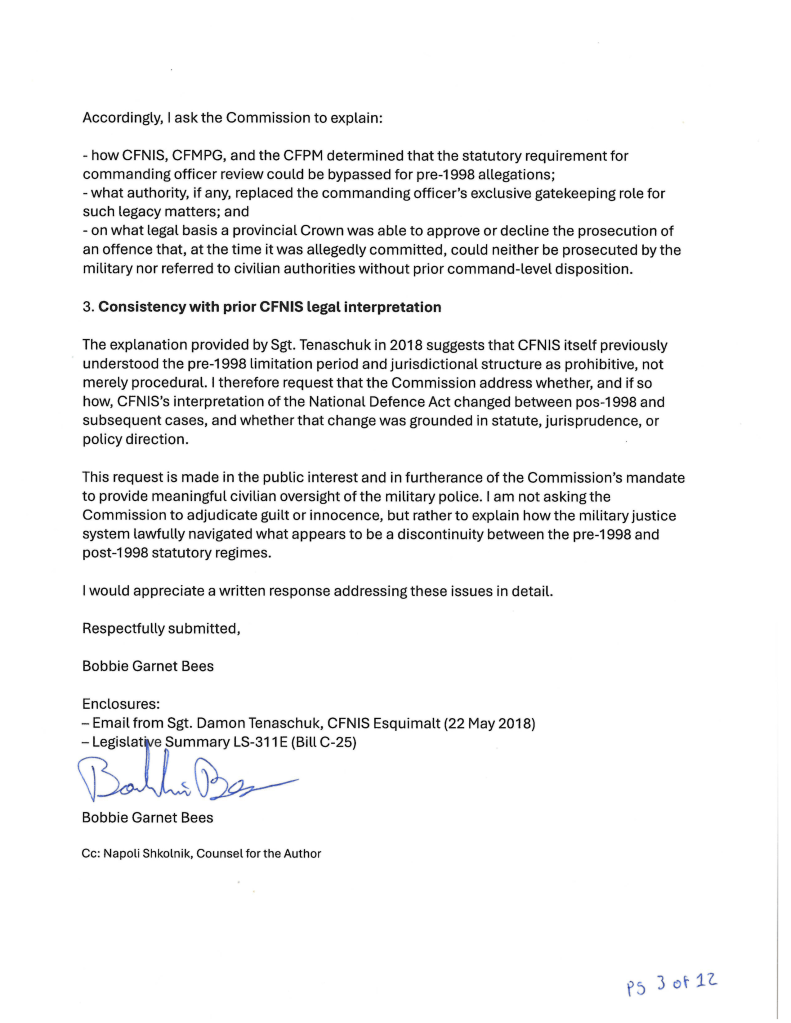

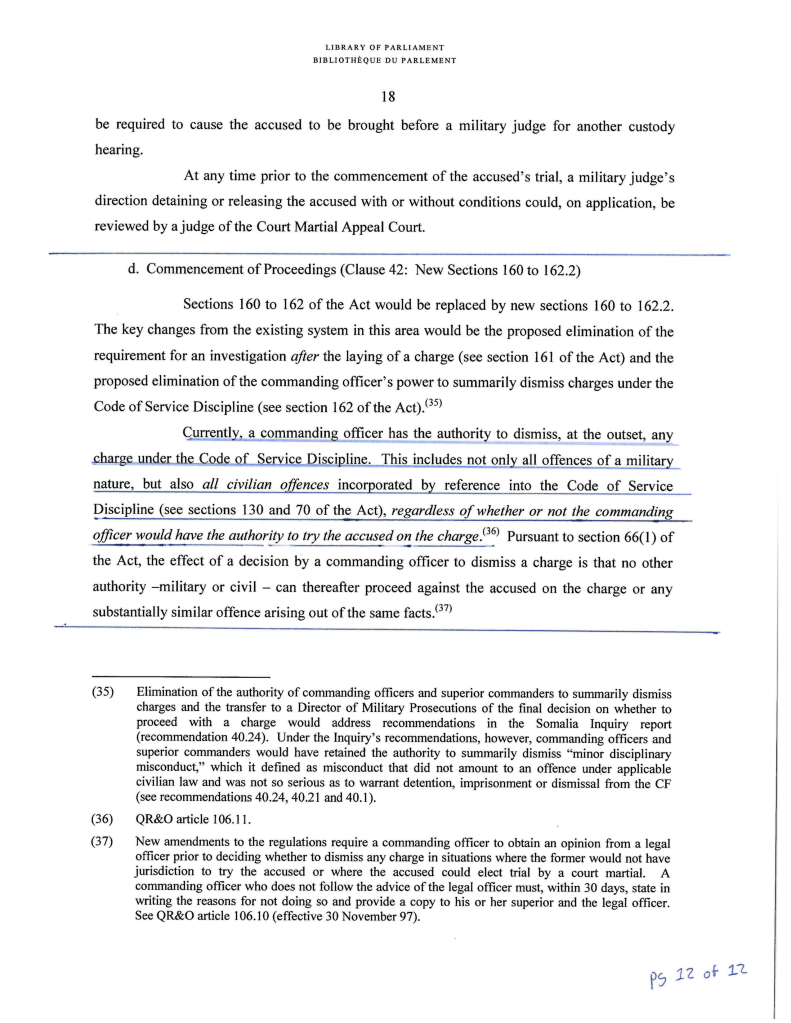

In the post Bill C-25 era, how do the Canadian Armed Forces and the Judge Advocate General reconcile with the fact that the accused could enjoy the protections presented by his commanding officer in a Summary Investigation that was required by the National Defence Act after the laying of charges?

It was the commanding officer’s discretion as to whether the charges would be dismissed, or moved to a civilian court or a military court.

How can the Canadian Forces Military Police or the Canadian Forces National Investigation Service in the modern day go against the protections that a member of the Canadian Armed Forces enjoyed prior to 1998 under the law.

You can’t simply pass legislation and strip rights retroactively. There’s a reason for this. In 1984 when “Rape” was removed from the Criminal Code of Canada, the charge of Rape wasn’t retroactively removed as this would have exposed generations of husbands to potential charges of rape as under the definition of rape in the Criminal Code, a husband could never be charged with rape for having forced sexual intercourse with his wife against her wishes.

When Stephen Harper raised the Age of Consent from 14 to 16 in 2008, there’s a reason why this law didn’t apply retroactively.

If the law was made retroactively can you imagine the chaos in the courts if suddenly 18 year old boy friends were going to prison for having sexual intercourse with their 15 year old girl friend, or vice versa?

If the Government of Canada were to remove the retroactive protections afforded by the pre-1998 National Defence Act you can bet that this would create quite the constitutional crisis in this country as now the government could pass laws at will that retroactively criminalized behaviours or retroactively removed protections.

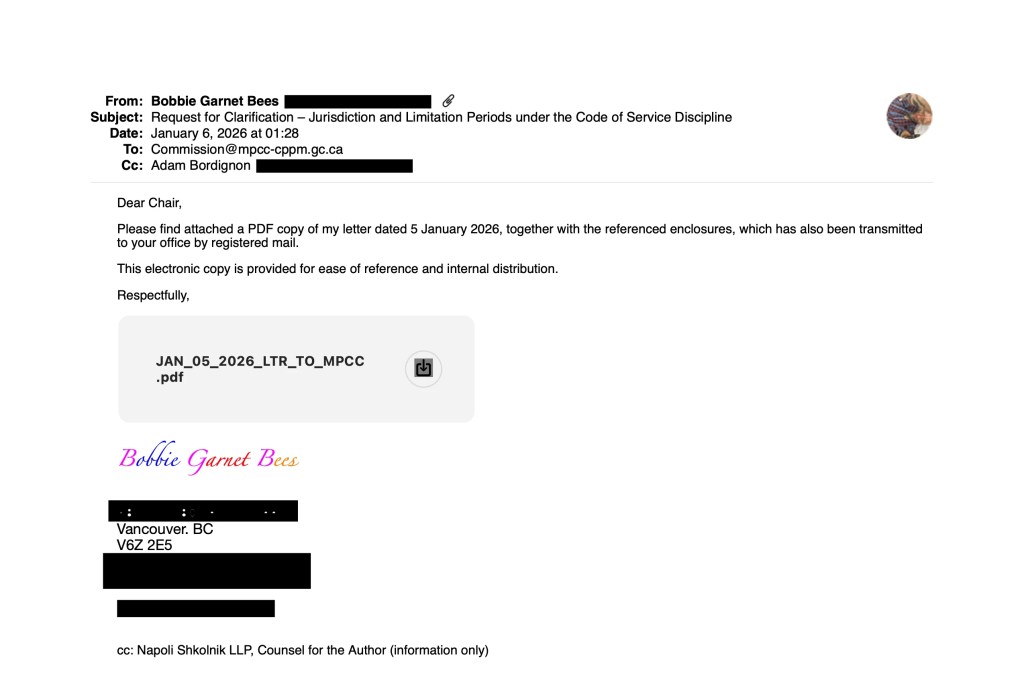

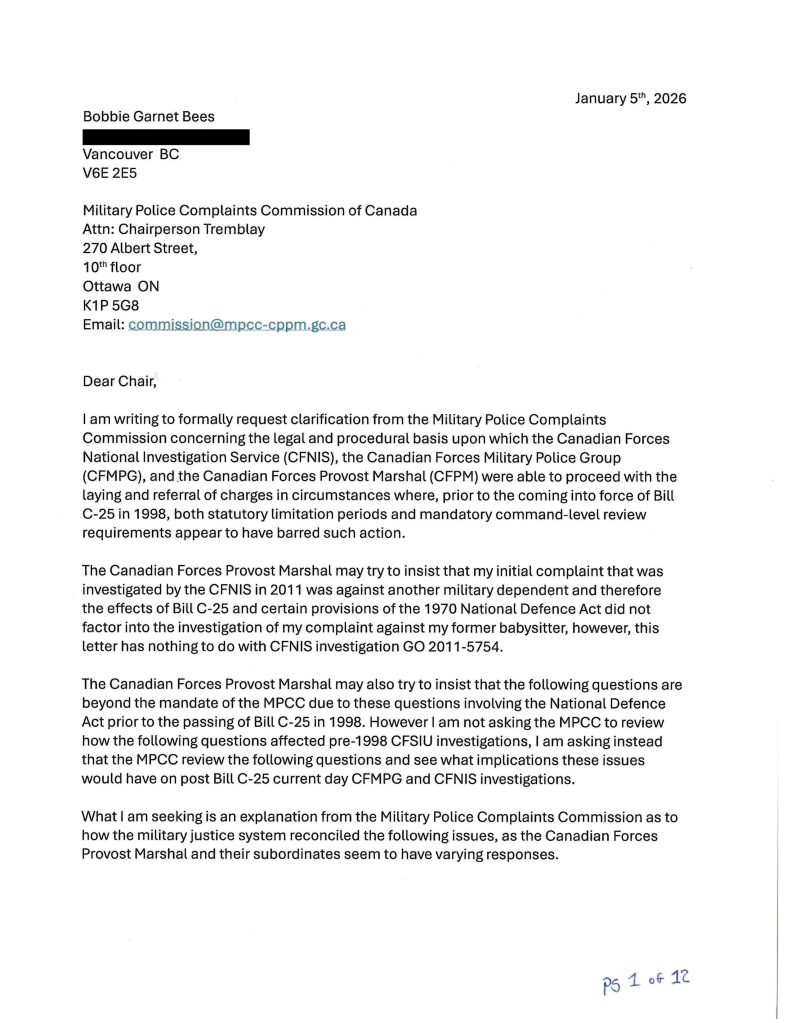

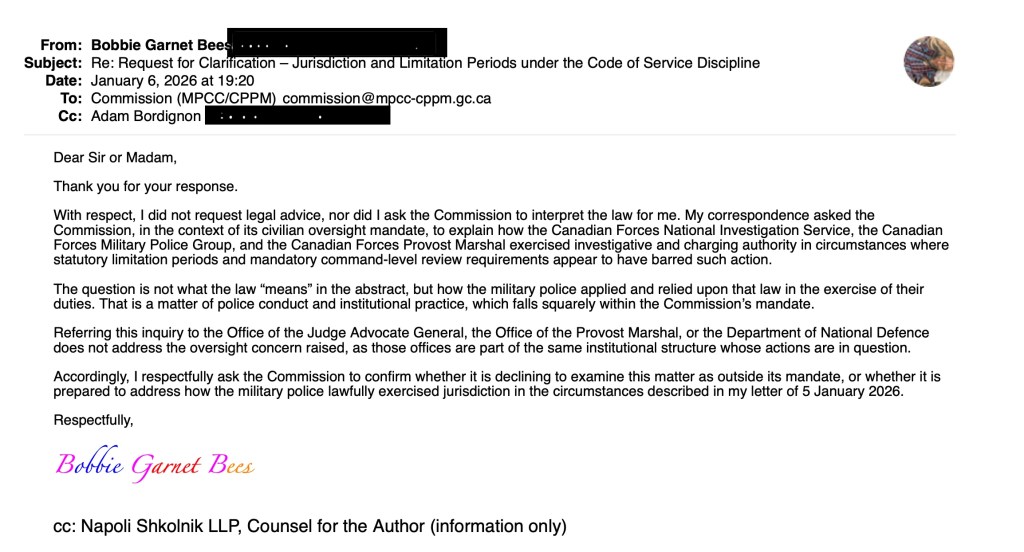

I sent a letter to the Military Police Complaints Commission asking them to look into how the modern day CFNIS was able to successfully lay charges for service offences that occurred prior to 1998.

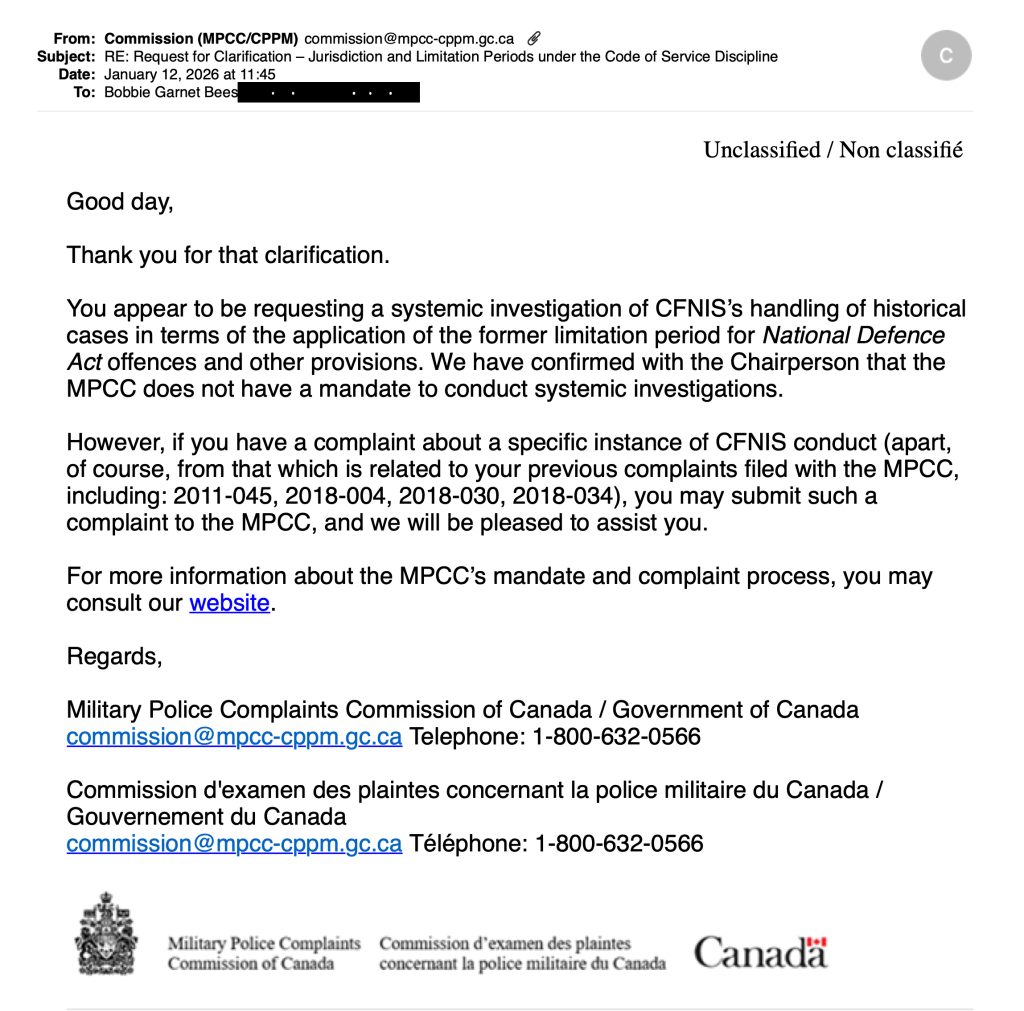

This is the response that I received from the MPCC:

I sent the following reply to their response.

And this was their final response:

The thing about the Military Police Complaints Commission that makes it very different from civilian police agencies is that you cannot make complaints against the CFNIS or any component of the Canadian Forces Military Police Group outside of conduct complaints related to the conduct of a specific person or persons during an investigation.

This is one of the ways that the Government of Canada compromised with the Canadian Armed Forces and got the Canadian Armed Forces to buy in to civilian oversight of their in-house police agency.

The military has its customs, and it sure as hell wasn’t going to allow some outside civilian agency to come in and tell the military police what they could or couldn’t do.

And Parliament, in draughting the rules for the MPCC, obviously never imagined the need for the MPCC to handle complaints from civilians about civilian related investigations undertaken by the CFNIS.

The rules of the MPCC favour members of the Canadian Armed Forces. If you’re a member of the public, you are shit out of luck, especially if you don’t have the funds available to hire an ex-JAG willing to go up against the Canadian Armed Forces.

And unlike members of the public, members of the Canadian Armed Forces can approach the Chief of Defence Staff with a grievance for redress that will override any finding of the Canadian Forces Provost Marshal or the Military Police Complaints Commission.

If I had to say what the number one flaw with the Military Police Complaints Commission is, it’s that during a conduct review the MPCC will not share with the complainant what the Canadian Forces Provost Marshal shared with the MPCC.

As I’ve said in other posts, the Canadian Forces Provost Marshal has the full authority under the National Defence Act to pull the wool over the eyes of the MPCC and there is nothing the MPCC can do.

The MPCC is full well aware that the CFPM more often than not hides paperwork from the MPCC and refuses to hand over documents.

In my matter, the CFNIS knew full well in March of 2011 of the connection between my babysitter and Canadian Armed Forces officer Captain Father Angus McRae.

The CFNIS already had the 1980 CFSIU investigation paperwork. The CFNIS also had the 1980 Courts Martial transcripts for the Courts Martial of Captain McRae. The CFNIS knew in March of 2011 from CFSIU DS-120-10-80 and from Courts Martial transcripts CM-62 that it was the investigation of my babysitter by the base military police in May of 1980 for the molestation of numerous children on the base that led to the investigation of Canadian Armed Forces Officer Captain Father Angus McRae.

The CFNIS in March of 2011 were very much well aware that the investigation of Captain McRae uncovered the fact that McRae and the babysitter hadn’t just molested a child or two. According to Mr. Cunningham in November of 2011, and the babysitter’s father in July of 2015, the CFSIU knew that Captain McRae and the babysitter were involved in molesting well over 25 children on the base from the years of 1978 to 1980.

In 2011 the CFNIS did a CPIC check on the babysitter.

The CFNIS would have discovered:

1982 – Convicted for molesting a young boy that lived off the base at CFB Petawawa.

1984 – Convicted for child molestation involving a child that lived off the base at CFB Winnipeg in Manitoba.

1985 – convicted for molesting a 9 year old boy on Canadian Forces Base Namao when his father had been posted back there. Also convicted for molesting a 13 year old newspaper boy after the Canadian Armed Forces ordered the babysitter to move out of the military housing.

The CFNIS, the Canadian Forces Provost Marshal, the Chief of Defence Staff, and the Minister of National Defence were well aware of the babysitter’s $4.3 million dollar civil action against the Minister of National Defence that was settled in December of 2008.

And yet, on November 4th, 2011, Petty Officer Steve Morris contacted me by telephone and told me that the CFNIS just couldn’t find any evidence to indicate that the babysitter was capable of committing the crimes that I had accused him of, even though I would find out in 2020 that the Courts Martial transcripts showed that the military police and the CFSIU knew that the babysitter was having forced anal intercourse with children much younger than he was and that he was receiving psychiatric care for his attraction to children even before he had been investigated by the base military police in May of 1980.

But, this is information that the Canadian Forces Provost Marshal willingly withheld from the Military Police Complaints Commission in 2012.

Doesn’t the CFPM worry that someone will discover what the CFPM did?

Nope. Why should they?

No agency has the authority to order the CFPM to hand over any documents. And to prove that the CFPM and the CFNIS don’t have “local copies” would be impossible.

But considering that the Captain McRae scandal has resulted in at least one successful lawsuit against the Minister of National Defence for the actions of Captain McRae, I wouldn’t put it past the military to have a folder or a CD-ROM / USB thumb drive / hidden network folder that contains instructions on how the CFNIS are to handle any complaints against Captain McRae or Captain McRae’s altar boys.

This way there’s no paper trail showing that the CFNIS signed out copies of the CFSIU DS-120-10-80 or the CM62 Courts Martial transcripts from the JAG library.

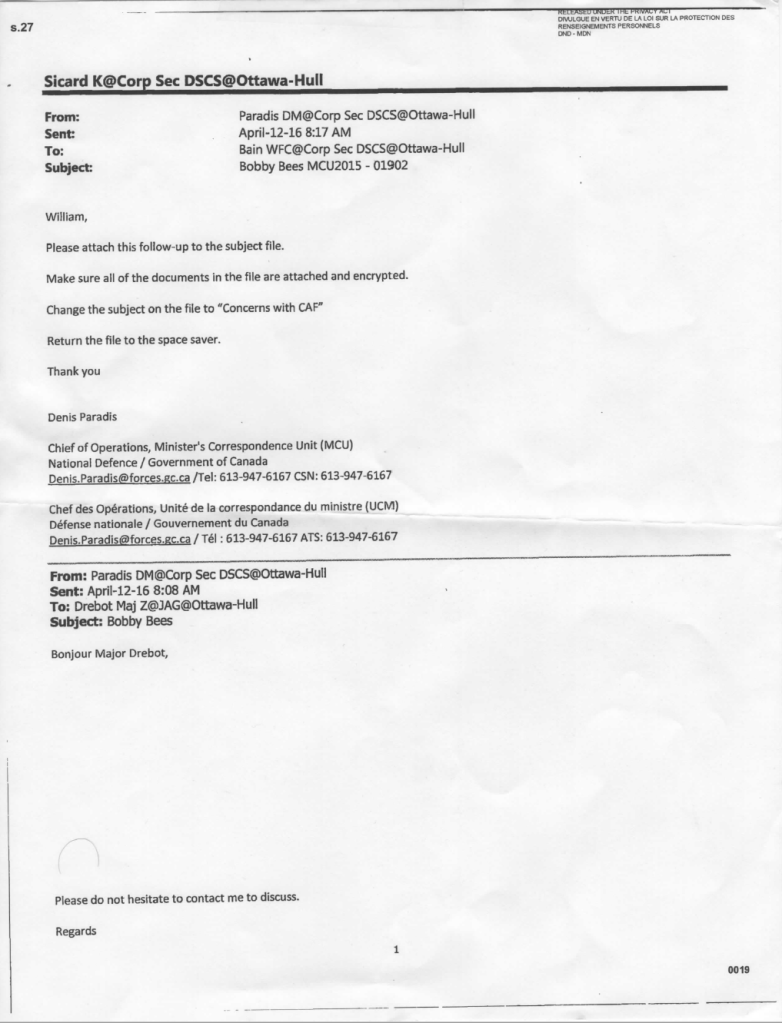

This is like when the Communications Officer for the Minister of National Defence asked for my correspondence to be given a non controversial name, encrypted, and hidden away in a “space saver file” ensuring that the contents were always beyond discovery and disclosure.

And when I filed my application for judicial review in 2013, when I discovered what the Canadian Forces Provost Marshal had done, it was too late.

This was the fatal flaw with my application for judicial review.

I relied extensively on “new evidence” which really wasn’t new evidence.

It was evidence that the Canadian Forces National Investigation Service had in their possession as it was information that I had shared with them, but it was evidence that the Canadian Forces Provost Marshal intentionally withheld from the Military Police Complaints Commission.

And during my dealings with the MPCC, the MPCC never once sat down with me and shared with me what the CFNIS had shared with them so that I could counteract what the CFNIS had claimed.

Instead MPCC investigators Peter and Claude both lectured me as to why the CFNIS had done one helluva bang-on investigation. Maybe Claude and Peter refused to accept my email conversations with the CFNIS investigators because they knew if these weren’t in the documents supplied to the MPCC by the CFPM they wouldn’t be able to do anything with them.

So…….. that leads to the question, “What is the purpose of the MPCC”?

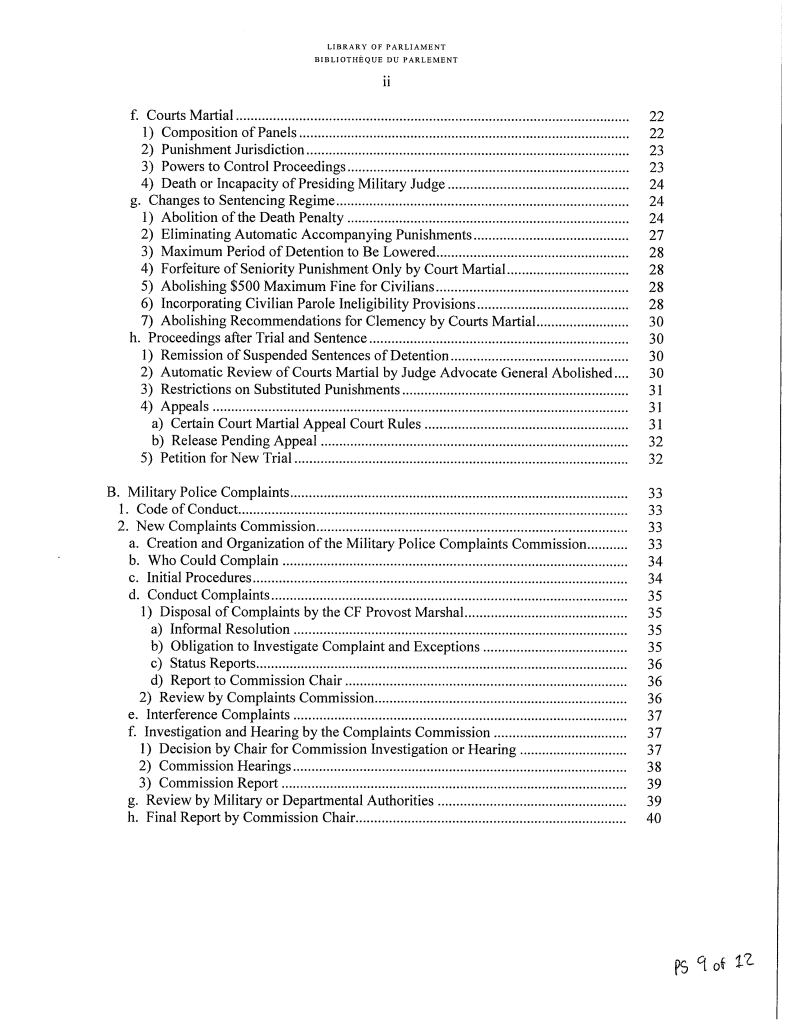

The existence of the MPCC is just to satisfy a checkbox in Bill C-25. And that was the establishment of an outside civilian agency to oversee the military police. And that’s it. That’s why the Canadian Forces Provost Marshal has absolutely no issue with thumbing its nose at the MPCC as the CFPM knows there’s nothing of any real consequence that the MPCC can do.

During a review the MPCC cannot:

Subpoena documents

Subpoena witnesses

Administer Oaths

Re-run the investigation to see if the CFNIS should have come to a different conclusion.

All the MPCC can do is to look at what the CFNIS did.

Did the CFNIS take my complaint ?

Did the CFNIS investigate my complaint?

Did the CFNIS talk to witnesses?

Did the CFNIS submit a brief to the Crown?

So when an investigator claims that he flew out to Victoria to personally meet with me, it’s not the MPCC’s job to ascertain if this is true or not.

And even though the CFNIS investigator lied, he would have faced absolutely no consequences for lying.

When the CFNIS excludes all of my social service records that indicate that my father had brought his mother into the PMQ on base to raise my brother and I because our mother “abandoned us” and that he subsequently blamed his own mother for being cruel and abusive towards his children due to her alcoholism, the CFNIS never call him to explain his statement that his mother never lived with us and that he never hired a babysitter.

The fact he never hired a babysitter is correct, but that’s only because he was never at home.

Rent on the PMQ was cheap. Much cheaper than renting grandma a three bedroom apartment off base in the city. If it would have been cheaper for grandma to live off base, Richard would have sent us to live with her. And not only was it just cheaper for grandma, Scott, and I to live on base in the PMQs, but Richard could continue to claim us on his income taxes.

And more importantly, as we lived on base, Richard could use the Defence Establishment Trespass Regulations to ensure that our mother wasn’t able to come to see us. It wasn’t that our mother “abandoned” the family on CFB Summerside, Richard had the military police eject her from the military housing as she wanted a divorce if he was unwilling to get his rage and his drinking under control.

And at the end of the day, there is nothing that the MPCC can do to discipline the CFPM or any member of the Canadian Forces Military Police Group. If the CFPM wants to ignore the findings of the MPCC, the CFPM can tell the MPCC to go piss up a rope. Any recommendations that the MPCC offer are not enforceable through any legal mechanism.