Well, stepped far out of the world that I’m allowed to exist in.

I’ve said before that I really don’t particularly care about computers.

Didn’t say that I didn’t understand them, just that I didn’t particularly care about them.

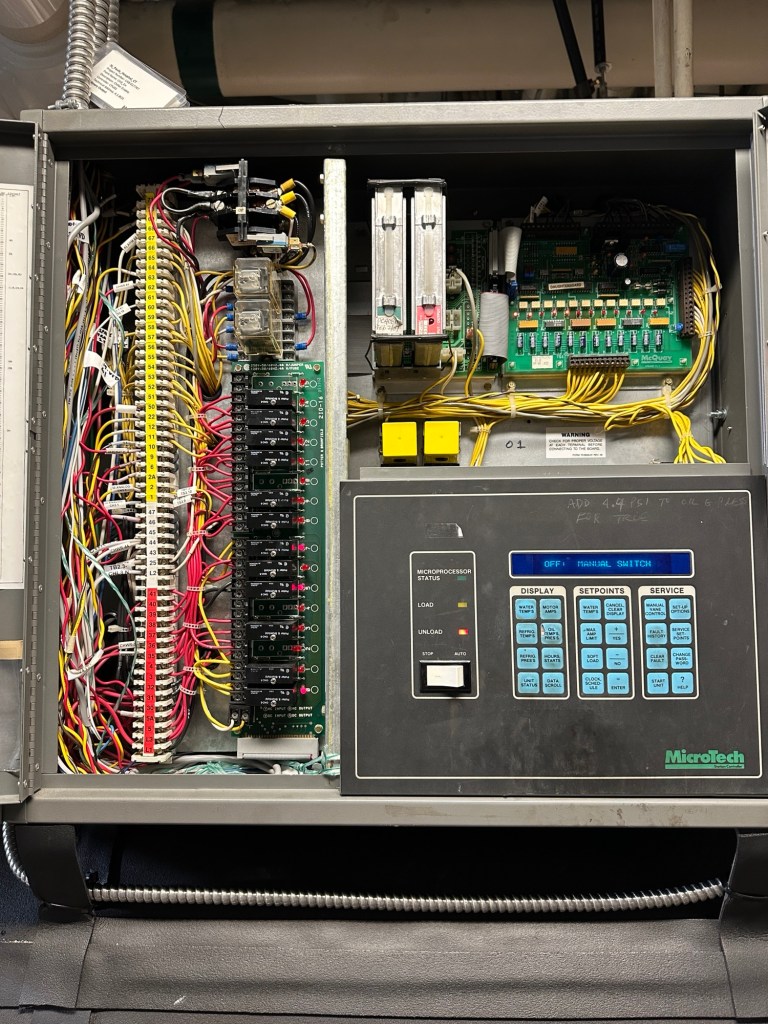

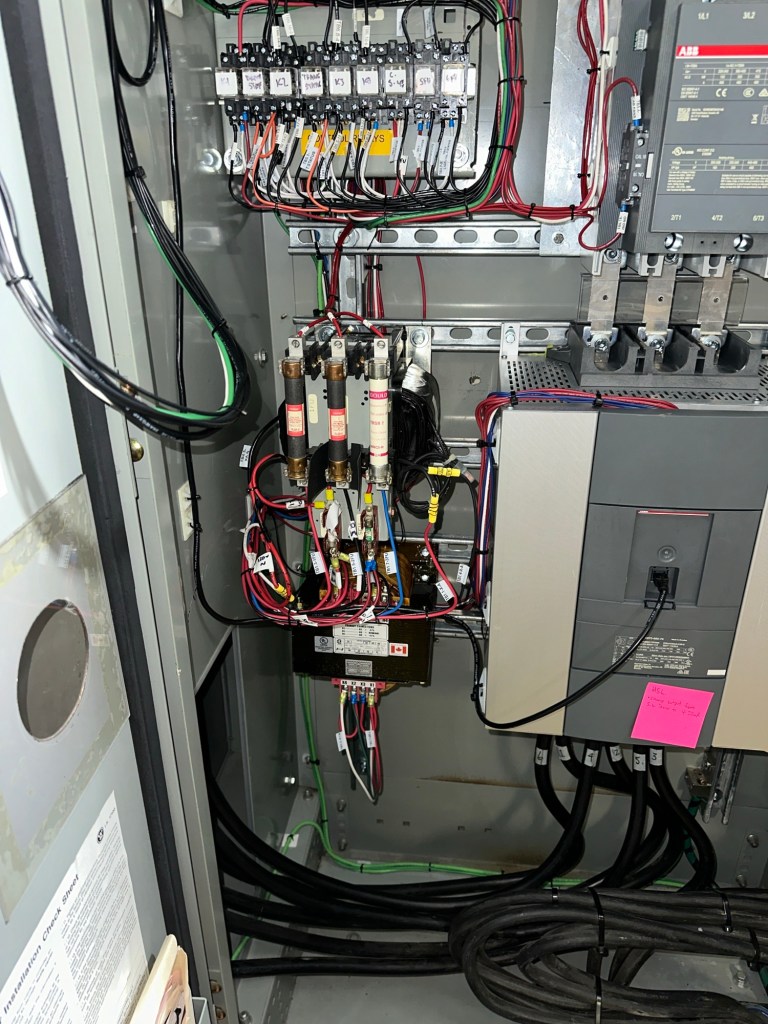

Recently one of the last remaining electro-mechanical elevators was modernized at the hospital. Due to a misunderstanding there was no provision for connecting the elevator to the existing monitoring system to allow the shift engineers to be notified when an elevator breaks down or when someone accidentally presses the alarm button but doesn’t stay to answer the operator, the engineer can prioritize responding to the elevator depending on if the system says the car is out of service or if the car is in service.

Anyways, to run a direct line from the elevator controller to the computer in the engineer’s office was going to cost about $10k to run the shielded CAT6 cable in conduit with about four holes that would need radiographs and coring.

Existing hospital network to the rescue.

The entire hospital is covered with CAT6. Each subnet on the network is basically a switch or gang of switches. The switches in use have 48 ports on them and the switches can be physically uplinked together giving the hospital at least 6 switches per subnet which is 288 ports, 286 when you take away the broadcast and gateway for the subnet. That’s 254 subnet ports + 32 ports that can be used by other VLANS.

So, lots of room for a measly elevator controller to traverse the network.

Isolation Meets Legacy Monitoring: A Practical NAT Story

For the sake of illustration, I’ll use the following fictional IP addressing:

NAT 1 (Engineer’s Office)

WAN uplink: 1.2.2.3

Monitoring gateway (LAN): 2.2.1.1

Monitoring workstation: 2.2.1.2

NAT 2 (Comox Building Elevator Closet)

WAN uplink: 1.2.3.4

Elevator B11 gateway (LAN): 2.2.2.1

Elevator controller: 2.2.2.2

My goal was straightforward: keep the elevator controllers off the main hospital user network, while still allowing structured monitoring traffic to traverse it. To solve this, I deployed a pair of Moxa NAT‑102 devices as dedicated Network Address Translation gateways between the monitoring workstation and the elevator controller domains.

Though NAT devices live in private space internally, they behave more like protocol-opinionated security routers than plug-and-play default gateways. Their firewalls operate in a default-deny, stateful inspection mode: inbound traffic is rejected unless it matches an existing outbound session or a specifically declared rule. In this architecture, flows are permitted because they originate from the monitoring workstation (the client) and are expected by the controller (the host) — not because broad inbound access was opened.

Here’s the packet walk:

- The monitoring workstation (

2.2.1.2) sends an outbound request for controller data, addressed to the remote NAT’s WAN (1.2.3.4) using the local closet NAT (2.2.1.1) as its next hop. - NAT 1 modifies only the source address, replacing the original host IP

2.2.1.2with its own egress IP1.2.2.3, and forwards the packet across the backbone to NAT 2. - NAT 2’s firewall permits the packet because a rule exists to allow flows from NAT 1’s WAN IP (

1.2.2.3) into its routing table. - NAT 2 routes the session internally to the Elevator controller LAN (

2.2.2.2) via its local gateway interface (2.2.2.1). - The elevator controller processes the request and replies with the requested data. The reply is not blindly broadcast across the LAN — it is returned inside the NAT session state table, allowing NAT 2 to map the translated session back to NAT 1.

- NAT 2 applies NAT in the same direction as the reply flow: replacing its own source

2.2.2.1with its WAN1.2.3.4, and sends the packet back across the backbone. - NAT 1 permits the inbound packet because it matches an expected reply from NAT 2 and then delivers it back to the original client (

2.2.1.2) through its LAN interface.

This design keeps critical OT equipment segmented, predictable, and unscannable from the wider network, while still allowing exactly one channel of monitoring truth to pass in and out. It’s not glamorous, but it works — and that’s often the most important engineering KPI in a 24/7 healthcare environment.

And thus the elevator LAN is isolated from the hospital LAN and vice versa even though they are directly connected to each other

The engineers can see the status of elevator B11 and can receive emergency email notifications when it breaks down.

Bobbie, you must be so proud of yourself!!!!!

For what?

As my father always said, it’s not like I built this shit. So why the fuck am I taking credit for something that somebody else created and made possible?

I didn’t build the fucking Moxa NATs.

I didn’t create the idea of using NATs to hide one private network from another private network.

I didn’t write the software on the monitoring computer.

I didn’t write the software on the elevator controller.

I didn’t create the Transmission Control Protocol / Internet Protocol.

I’m not a genius.

I’m not a geek.

I’m just doing something that anyone can do.