Let me be very clear about something.

Modern psychiatry is not primarily about repairing damaged minds. In practice, it is far more often about teaching damaged people how to function quietly—how to mask distress, suppress history, and remain acceptable to everyone else. Recovery is measured less by relief from suffering than by how little discomfort one causes others.

If you’ve followed my story, you’ll know that my first sustained contact with psychiatry and social services came in 1980 during the aftermath of the Captain Father Angus McRae child sexual abuse scandal on Canadian Forces Base Namao.

Three Systems, One Child

During that period, I was trapped between three systems, each with competing priorities:

- the military social work system,

- the civilian child welfare system, and

- a deeply dysfunctional family, headed by a low-ranking CAF member struggling with untreated psychiatric issues, alcoholism, anger, and fear for his own career.

My civilian social workers recognized that my home environment was harmful and attempted to remove me from it. My military social worker, however, worked just as hard to prevent that outcome—not because civilian foster care was inherently worse, but because civilian intervention threatened military control of the situation.

This distinction matters.

Because my family lived in military housing on CFB Griesbach, Alberta Social Services could not simply enter the base and remove me. Civilian court orders had little practical force on base. Jurisdictional ambiguity worked entirely in the military’s favour.

Containing the McRae Scandal

At the same time, the Canadian Armed Forces and the Department of National Defence were doing everything possible to keep the McRae scandal minimized and out of public view. The decision to move McRae’s court martial in camera—despite the general rule that courts martial are public—was not incidental.

From an institutional perspective, it was far more convenient to present the case as involving a single fourteen-year-old boy, the then-legal age of consent in 1980, framed as “homosexual activity,” than to acknowledge the reality: more than twenty-five children, some as young as four.

Under military law, sentences were served concurrently. Whether McRae abused one child or twenty-five, the maximum punishment remained the same. The difference lay only in public perception.

Blame as a Containment Strategy

This context explains much of what followed.

Captain Totzke, the military psychiatrist assigned to me, appeared deeply invested in ensuring that I—not the system, not the institution—was framed as the source of dysfunction. Civilian social workers were treated as adversaries. The unspoken fear was that if I were removed from my father’s care and placed into foster or residential care, I might stabilize, improve, and begin speaking openly about what had happened on CFB Namao.

Instead of being treated for trauma-induced depression, I was told—explicitly—that I suffered from a mental illness called “homosexuality.” I was warned that I would end up in jail. I was told I was a pervert for having “allowed” my brother to be abused.

I was informed by Captain Totzke that he had the military police watching me, and that any expression of affection toward another boy would result in confinement at a psychiatric hospital. I was barred from change rooms, removed from team sports, and excluded from normal childhood activities under the justification that I could not be trusted to control myself even though I had been the victim of the abuse and not the abuser. In the military’s lens at the time, any sexual encounter between two males, no matter the age difference or the lack of consent, was treated as an indication of homosexuality. The victim was just as guilty as the perpetrator.

Age and Diagnosis

I was six years old when my family arrived on CFB Namao. I was eight when the abuse was discovered. Psychiatric intervention began about four months later just after my 9th birthday. By that point I was diagnosed with major depression, severe anxiety, haphephobia, and an intense fear of men. My father was so angry with me for having been found being abused that I was terrified that he was going to kill me.

None of these conditions were meaningfully treated.

What I did learn was how to perform wellness—how to mask distress just well enough to avoid punishment. That skill would define my later interactions with mental health professionals and the world in general. When I’d go for counselling with my civilian social workers, my father and Totzke would often warn me to watch what I said to the civilian social workers as they’d “twist my words” to make it sound as if I had said things that I didn’t say.

The Mask Never Comes Off

For decades afterward, my attempts at counselling followed a familiar pattern. My history was unwelcome. My symptoms were reframed as resistance. The stock phrases appeared reliably:

- “Stop living in the past.”

- “Move on.”

- “You don’t want to change.”

- “You’re playing the victim.”

It was not until 2011, when I finally received my own records, that I understood how early—and how thoroughly—my life had been derailed.

Group therapy or one-on-one it didn’t matter. Especially back in the days before I had obtained my social services paperwork. My inability to get out of bed on consistently was just because I’d stay up too late. My ability to sleep for days on end and miss work was just because I was a lazy asshole. My preference to be left alone was nothing more than my superiority complex. My debilitating fear of courses and exams wasn’t due to low self esteem, hell no, it was that I thought that I was too good.

Medical Assistance in Dying

For a while now I have been very open about my desire to access Medical Assistance in Dying.

What continues to astonish me is how many people believe this wish can be dissolved through optimism, pharmacology, or spiritual novelty. Ketamine infusions, microdosing, mantras—anything except acknowledging that some damage is permanent, and that survival itself can be a form of ongoing harm.

Don’t forget, in my case it wasn’t that the sexual abuse was unknown and no one ever knew about the issues I was facing. The CFB Namao child sexual abuse scandal was well known about in the military community. My diagnoses were known to my father and to Captain Totzke. But I wasn’t allowed to receive any help due to the desire to keep the proverbial “lid on things”.

Statistics and Comforting Fictions

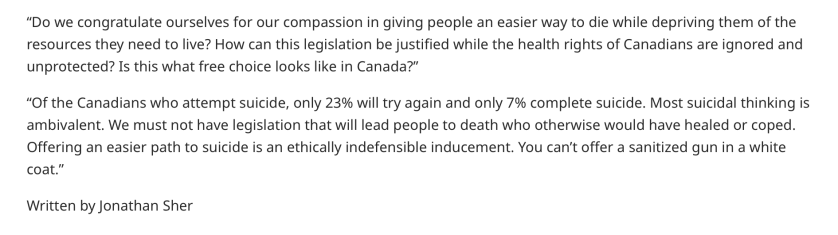

This is why much of the anti-MAiD commentary rings hollow.

Recent opinion pieces lean heavily on selective statistics about suicide attempts and “recovery,” while ignoring the realities of under-reporting, stigma, misclassification of deaths, and survivorship bias.

Suicide statistics rely on narrow definitions: notes, explicit intent, immediate death. Overdoses are coded as accidental. Single-vehicle crashes are ambiguous. Deaths occurring months or years after catastrophic attempts are often excluded entirely.

The result is a comforting fiction.

A failed suicide attempt is not a victory. Often, it is survival driven by fear—not of death, but of catastrophic impairment. That fear should not be celebrated as evidence of restored hope or desire to live.

What Psychiatry Refuses to Admit

If psychiatry were being honest, it would admit what it does not know: the precise causes of depression, why some people do not recover, why treatment sometimes merely dulls experience rather than alleviating suffering.

It would also acknowledge the role of compliance and performance—the pressure to appear “better” so as not to be labeled the problem.

Instead, responsibility is quietly transferred back onto the patient.

And that, more than anything, is what I am unwilling to accept anymore.

Recently in the Toronto Star was an opinion piece

M.A.i.D. really isn’t an issue that requires “both sidesing”, but that’s what this opinion piece strives to do. It tries to mush a person’s right to self determination with personal opinions. And sadly the writer of the opinion piece concludes that if Canada could only fix its mental health system, then everyone would live happily ever after

Dr. Maher is dead set against M.A.i.D., to him any psychiatric illness can be easily treated, and if it can’t then the person should simply hold on and wait for a treatment that might possibly eventually work.

Dr. Maher was interviewed for an article published by the Canadian Mental Health Association.

I have some questions for Dr. Maher.

23% of what? What is the number of Canadians that attempt suicide? 10 people, 100 people, 1,000 people, 100,000 people? How many people are we talking about?

Do we even know how many people attempt to commit suicide every year?

How many overdoses or single vehicle collisions are actually suicides?

How many people killed during risk taking activities are actually suicides?

How many work place “accidents” are actually suicides?

How many times does the coroner resist calling a death a suicide to spare the family the stigma of a suicide death?

How many times does the lack of a note cause the police and others to overlook a suicide?

How many people attempt suicide only to back away at the last moment, not out of the fear of dying, but out of the fear of fucking it up and ending up living for 20 years as a vegetable in a nursing home?

How many people that have attempted suicide never try to commit suicide again, not because they don’t want to take another attempt, but because their first attempt left them either physically or cognitively unable to make another attempt?

I guess we’ll never know.

And that’s sad.

This lack of understanding allows suicide to be pawned off as some random irrational behaviour that is driven by temporary bouts of sadness that some people just get too hysterical about instead of admitting that the human brain has an actual breaking point that once crossed can never be uncrossed.

I have flirted with the idea of applying for MAID myself and I really do understand where you are coming from! Having a bit of personal connection with your upbringing, I can verify that what you endured is true! My kids, as well, suffered a lot from a Dagenais family member. So, we definitely connect.

LikeLike

Speaking of which.. I definitely have ‘passive suicidal ideations!’. I just think that sometimes it would be ideal for me to die and make little effort to ‘save’ myself. It doesn’t do much for me, though, because it really is harder to die than we think! Already signed a DNR….

LikeLike

I just did a google search to see if my story was ever published in the media. No, nothing, but I found this post. I see you friend. I know it doesn’t necessarily mean anything from a stranger on the internet, but I’m sorry you went through what you did.

My abuser wasn’t McRae and it was not of a sexual nature, but I was directly impacted by him. I am both completely disconnected from what you experienced, but still intimately involved in this story. My abuse came at the hands of my Kindergarten teacher, a Madame Garigliano (I don’t even know her full name) at Greisbach Elementary in 1992. The only proof I even have that it happened is the police reports and witness statements that my mother kept; witness statements dictated by adults, but signed in crayon by the actual witnesses, my 4/5 year-old my classmates. I guess I have the memories too, but those are difficult to point to.

Your story is eerily familiar. Your experiences and commentary are your own, but also incredibly resonant…

The opposite of you, I lived in Namao (then Lancaster Park) and my parents sent me to Greisbach for the French immersion experience. Like you, my father was just a Private at the time and had no real authority in his position. When my abuse was finally reported, the CAF did everything they could to just brush it all under the rug. They were worried about a repeated scandal hitting the news, I was only vaguely aware of what that was until today. They didn’t want this one going out to the media so they begged my father to keep quiet… He did.

In an effort to be fair to you, I should be clear, I don’t want it to sound like what I went through was the same. My abuse came in the form of daily physical abuse from both the teacher and other students. I was the classroom’s whipping boy. Where other children sat at large tables of 10+ students, I had a designated seat a the front of class (literally beside my abuser facing the other students). Anything wrong to happen in our class would be deemed my fault, where I would be expected to pay for it. My parents ignored the bruises, they ignored the nightly crying, they ignored my pleeding for months. They only acted after the school nurse reported what was happening. My arm had been ripped from its socket while she was throwing me across the room by it. My right shoulder and muscles in my neck are still constantly in pain, and only getting worse with age.

My parents were not abusive in response to this, but they were neglectful. My mother decided to frame the abuse as something she suffered, and my father just told me to grow up. A 5 year old boy. They treated me as if I was a broken toy that they didn’t want anymore. I was not allowed to go to therapy because they were worried I might speak negatively about them. I left home the moment I was able to.

My life has been riddled with the anxiety caused by those experiences. I’ve only ever had a handful of friends (only two whom I’d even call “close”), romance has been all but non-existant. It’s been lonely. I too have made multiple attempts at my life, and I too have been watching MAID closely. In fact, my last fight with my father is that he found out I was in favour of those with severe mental health disorders to seek MAID as a way out.

Botched suicides are a far more horrific concept than someone being given a safe and respectful way to end things.

Although I likely won’t seek it for myself (my overwhelming sense of nihilism has caused me to no longer seek suicide), no one should be forced to live in a world they don’t feel welcomed by. I understand you completely.

You may feel differently than I do about this, but I realize that my real abuse came as the result of the insecurity of those in power. Those who were unwilling to just address the abuse of children. Instead choosing to make it about themselves. You had your power stolen from you, I hope you can find a satisfying conclusion to your story, on your terms. Regardless of what that might look like.

Again, I am so incredibly sorry for your experiences. Thank you for sharing your story, thank you for advocating for yourself. Thank you for advocating for me… I may not visit this page again as this was difficult and I may not be as strong as you are. Honestly, this is the first time I’ve shared most of this with anyone…

If this is goodbye, then goodbye.

LikeLike

Hi Blink,

Thank you for trusting me with something this personal. I believe you, without hesitation. What you described — the isolation, the scapegoating, the physical harm, and the way adults closed ranks instead of protecting a child — is real, and it leaves marks that don’t fade with time.

What happened to you also fits a larger pattern that existed in the dependent school system at the time. Those schools sat in a legal grey zone: physically on base, but dealing with civilian children, which meant outside police and social services often had to go through the chain of command to intervene. Reputation management too often came before child safety. That reality is one of the reasons the CAF ultimately handed those schools over to civilian boards after the 1993–94 school year.

None of that excuses what was done to you. It only explains how institutions failed children repeatedly — and quietly.

You didn’t deserve what happened. You’re not imagining it, and you’re not alone in it. If this is goodbye, I respect that, and I’m grateful you chose to speak here at all.

LikeLike